Lessons from the past can help all of us build a better future

By Andy Barnett

A few of us at Asheville Habitat have been reading Heather McGhee’s book The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together. McGhee uses public swimming pools as a metaphor for her thesis that zero-sum thinking about race creates policies that hurt the whole community.

In the 1920s and 30s, communities around the country built top-of-the-line public swimming pools. These pools were a source of civic pride and status. Yet cities decided to drain their public pools rather than integrate them. They penalized the entire community rather than expanding public benefits to everyone.

My temptation whenever I learn disturbing history like this is to push away. Sure, that happened in places mentioned in the book like Montgomery, Jackson, and St. Louis. We know those places to be outliers of racial extremism…right?

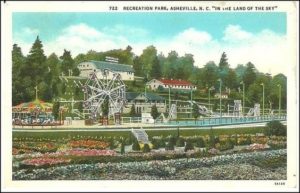

In 1922, Asheville built the Recreation Park. It included a public swimming pool as well as a dance hall, skating rink, a lake, shooting range, Ferris wheel, merry go round, tennis courts, playground, and later a zoo. The park was sited near the municipal golf course and the racially-restricted neighborhood of Beverly Hills, then under construction. Improvements to the pool and park continued through the depression. The pool was rebuilt following the parks closure during WWII.

postcard of Asheville Recreation Park, 1926

Although funded by all the taxpayers of Asheville, the pool and park were accessible only to whites. In the 1930s, the Buncombe County Negro Agricultural Fair Association raised private contributions to build a park and pool in the Shiloh neighborhood while the city opened the Walton Street pool for black swimmers.

In 1954, local attorney Harold Epps, the pastor of Berry Temple, and others petitioned council to integrate the pool and park. In response, the Asheville City Council closed the pool. They ordered it drained and filled to, according to their statement, “avoid any possible racial clash”. The following year, the city sold the pool to a private club who reopened it for whites only.

Asheville Recreation Park, 1939

If you’ve read this far, I bet you’re asking “what does all this have to do with affordable housing”? The same zero-sum thinking that led us to “drain the pool” shows up in housing, too.

Today, our whole community suffers from the lack of housing. Black and white, low wage earners and middle income households struggle to find a home they can afford. Yet, for almost 50 years, racial stereotypes of poverty have been used as excuses to gut federal investments in housing and prejudice the market against those who pay for a part of their housing through public investment. We drained the whole housing market of resources because we didn’t want some of our neighbors to “swim” in it.

McGhee encourage us to replace zero-sum thinking with the concept of a “solidarity dividend”. This is the idea that by attending to the common good–beginning with those who have been left out of it—we can build healthier, more vibrant communities for all of us. Habitat’s origin provides a tangible example. The building blocks of Habitat’s program—owner and community-built homes, affordable mortgage terms for very low income buyers—existed in federal programs before Habitat. Local administrators denied Black applicants in rural Georgia access to those programs. The partners at the Koininia community stepped into that gap and from there, Habitat for Humanity was born.

This spring, Asheville will break ground on a new public pool in the Southside neighborhood. Hopefully, it reminds us of the kind of community we can still create when we reject the lies meant to divide us and erode our investment in the common good.